Youth activists call for safer streets in Maputo

Date:

At 6 a.m. every morning, 13-year-old Jareeyah* from Maputo sets out for a 10-minute walk from home to her high school. The trek isn’t long, but it always makes her uneasy.

“Sometimes I walk with friends… I don’t feel safe in my city,” she says.

Jareeyah lives in the densely populated neighbourhood, Ka Maxakene, in the heart of Mozambique’s sprawling capital, Maputo.

In 2016, shortly after Maputo launched a Safe City and Safe Public Spaces Programme, as part of UN Women’s Safe Cities Global Initiative, a scoping study on sexual harassment and other forms of violence against women and girls in public spaces was conducted. Shockingly, it revealed that nearly 7 in 10 girls have experienced some form of violence in public spaces.

But girls like Jareeyah, a staunch feminist and human rights activist since the age of 9, are working on ways to change the situation. Through a leadership group at her school, Jareeyah organizes debates to get students to reflect on social problems including: gender inequality, sexual violence in public and private spaces, premature and forced marriage, urban insecurity, unsafe infrastructure, sanitation and safety in schools.

“We also talk about female leadership and safe spaces,” she says. “We can use our voices to advocate, raise awareness among other girls about where we can go and how we can live without violence, discrimination, or being insulted.”

Jareeyah carries a camera to snap images of insecure spaces and uses her voice, art and social media networks to advocate for infrastructure changes—and for girls to play a greater role in decision-making and designing gender-sensitive public policies.

It’s all part of the Maputo Safe City Programme, supported by the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation and the City of Madrid. The first action of the programme has been focused on activities in two schools, engaging young people and community champions to change attitudes and behaviours that hinder women and girls’ safety in public spaces.

“Just because they are girls, boys would touch their private parts and they were exposed to unwanted, tedious comments by men,” explains Jareeyah’s high school teacher Adelina Stela Manuel Chambal. “But this is changing after boys become sensitized through the debates. They’ve now started respecting girls, they understand that women’s/girl’s bodies can’t be touched without their permission, and they have learned to interact more respectfully with girls.”

As many as 25,000 community members are expected to be reached through awareness-raising activities in the neighbourhoods of Ka Maxakene and Kamalhanculo. Some 2,000 boys and girls are also engaged in these school-based activities.

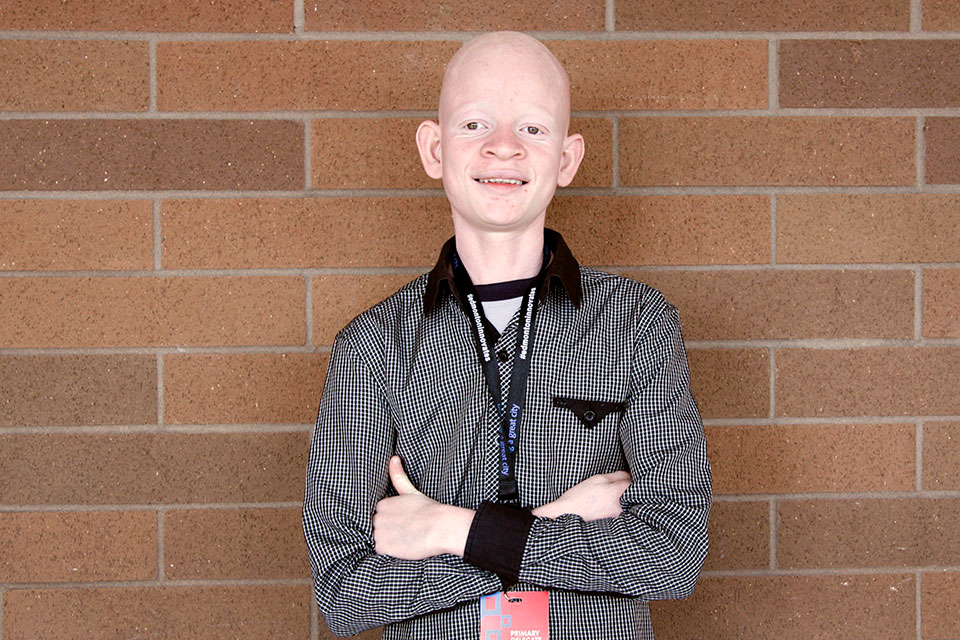

Among them is Frenk*, a 14-year-old human rights advocate and coordinator of the male engagement programme to end sexual violence in public spaces, at a high school in Ka Maxakene.

“Girls may get robbed, or raped. It happens often. Not a day goes by that you don’t hear about it on the TV news,” he says. “For Maputo to be a safe city we need to create more safe spaces. We talk among us guys and girls, about what we need, like more lighting in our neighbourhoods and also suggestion boxes where we can safely report violence.” In Frek’s school, a suggestion box is now in place, where students, teachers and workers can anonymously report any complaint, which is then addressed by a designated authority and the school management.

Frenk organizes thought-provoking discussions among his peers about toxic masculinities and how to transform them for positive change.

“Boys need to change the machismo culture and stop seeing themselves as powerful or violent, and regard girls as equal,” he says.

The Maputo Safe City Project Manager at UN Women Mozambique Fernanda Bernardo explains that these discussions are a starting point where girls and boys begin to question the norms and behaviours they were brought up with. “We have boy and girl leaders challenging these norms with other boys and girls, inviting them to join the reflections and be more active in disseminating positive values and masculinities,” she says.

Frenk divides up the girls and boys to separately discuss issues like gender equality, gender-based violence, social norms and power, before bringing them together to reflect on their role in creating safer communities.

“We promote debate and awareness to break the cycle of violence. We can all work to make our community more secure,” says Frenk. “I tell them we can be leaders in fighting against violence and using our voices to advocate.”

And their voices are being heard. Using a methodology called Photovoice, students have been taking pictures of the places they consider unsafe and making presentations to the community and government authorities.

Looking at urban planning and infrastructure with a gender lens matters because they impact the daily lives of women and girls—from their mobility to their access to sanitation, or how late they can stay outside and what jobs at what hour they can take.

“Because of the pictures, this issue became more visible and issues are being responded to,” explains Ms. Bernardo. She says that at Frenk’s school, students managed to get the school to change the location of the toilets because they were not private or safe for girls.

Young activists are even getting reactions to their complaints and demands from local authorities. One of the demands in Ka Maxakene was that the municipality illuminate unsafe streets and alleys. Community leaders also complained about an abandoned school to the Ministry of Education, and some staff from the Ministry visited the site, along with students to assess the situation.

Another action for the Maputo Safe City programme is focusing at the national level, as UN Women, teachers and students are advocating for a law against sexual harassment, particularly in schools.

Maputo is among the more than 37 cities that are taking part in UN Women’s Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces Global Initiative The Maputo Safe City Programme with Women and Girls was designed and launched in partnership with Maputo’s local government, the Ministry of Gender, Child and Social Action, UN Women, UN Habitat, Horizonte Azul, Men for Change Network (HOPEM), the Office of Technical Cooperation, Spain, women’s organizations and other key stakeholders.

*The full names of the beneficiaries have been withheld to protect their identity.