Why investing in women’s organizations is critical during crisis: Five stories of resilience

There are 614 million women and girls living in conflict affected areas today. From Palestine to Ukraine, Haiti, Sudan, and Afghanistan, their numbers are going up, as geopolitical conflicts, climate change, health and food crises intensify.

When crisis hits, women and girls experience increased risk of gender-based violence and loss of property and income. In fragile contexts, women and girls are nearly 8 times more likely to live in poverty than men, and in every region of the world, they are more food insecure. Yet, the financial and aid infrastructures continue to fail women, with devastating consequences. Less than one per cent of official development assistance (ODA) is going directly to women’s rights organizations. Making reliable, flexible, and multi-year funding accessible to local women’s organizations is urgent.

From the rubble in war-torn countries to the battlefields of climate change and economic crisis, women’s organizations provide critical services, hope, and a lifeline to their communities. In the words of five inspiring women, learn why investing in women is the way forward to a healthy planet, peaceful communities, and just economies.

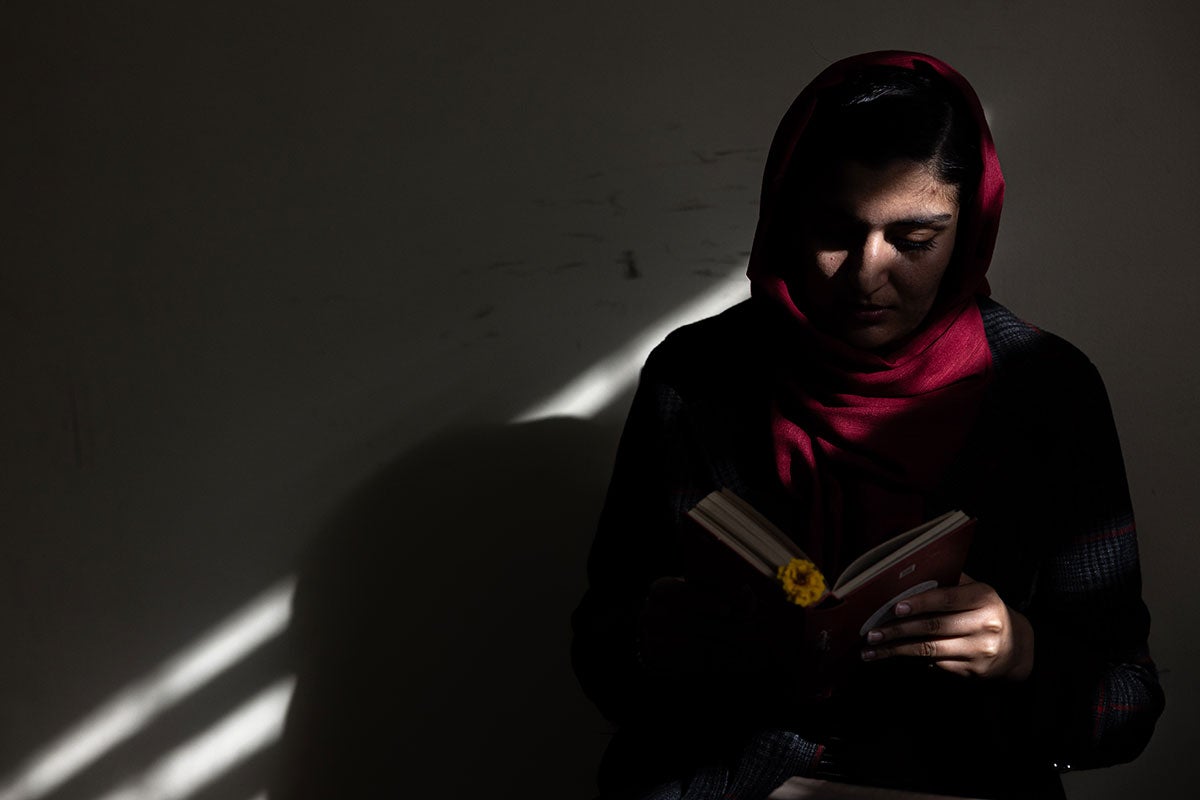

Building back the women’s movement in Afghanistan

“I will continue to stand strong, as a woman, supporting other Afghan women,” says Mehrgan*. The 37-year-old former teacher and school principal from Kunduz Province assesses women’s needs for developing entrepreneurial projects as part of a non-profit women-led organization. Its activities were significantly curtailed by the Taliban’s 2022 ban on women’s work.

“We train women on handicrafts as a means to start a home business; we work on agricultural development, with projects to help illiterate women or those who cannot work; and we do what we can so that women can access some form of education.”

“Before 2022, our organization was so active. We taught women, hundreds of women benefited from our work. We also created a network of local women’s NGOs and organized monthly meetings where we shared our experiences.”

When the Taliban banned women’s work in [non-governmental] organizations in 2022, the organization lost its funding and from 24 full-time staff, they went down to eight. With UN Women’s support in late 2023, they have restarted some projects.

“I go to remote areas and collect [women’s] stories, take note of their needs, listen to their problems, and this gives them hope. I try my best and that also gives me hope.”

With training from UN Women on strategic planning and project management, Mehrgan’s organization has improved its organizational plan, budgets and policies.

“I just trained another local women’s organization in Kunduz about this,” said Mehrgan, showing how a small investment in women’s organizations can strengthen so many more.

UN Women is supporting 86 women’s organizations under its ‘Rebuilding the women’s movement in Afghanistan’ programme, with contributions from the governments of Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Belgium, Spain, and Austria.

* Names, locations, and details have been changed to protect the identity of the protagonist. She is not displayed in the accompanying photo.

Women’s organizations provide a lifeline to women in Gaza

More than 2 million Palestinians in Gaza face inhumane living conditions today. Gaza has become a protection crisis for women, with close to one million women and girls displaced and two mothers killed every hour, since the beginning of the crisis.

Yet, women-led and women’s rights organizations continue to operate, providing a lifeline to the communities where they work. UN Women’s analysis shows that 83 per cent of women’s organizations surveyed in the Gaza Strip are at least partially operational, mainly focusing on the emergency response. However, just 0.09 per cent of funding to the 2023 Flash Appeal has directly gone to national or local women’s rights organizations.

“Our main office is in Gaza City, which has been [damaged] by Israeli military bombardment. Due to safety concerns, we cannot assess the full extent of the damage,” said Amal Syam, General Manager of Women’s Affairs Center (WAC).

Before the Israeli military bombardment of Gaza started in October 2023, the Center employed 100 staff and assisted more than 170,000 people every year.

“To support the people of Rafah, where around 1.5 million are seeking safety, we opened a new office at the center of Rafah,” Syam shared. We have provided humanitarian assistance to women, including psychological support, legal counselling, and distributed cash assistance, hygiene and dignity kits.”

The Center aids the most vulnerable, shares stories of women’s experiences, and is documenting the war's impact and women's urgent needs.

Hundreds of women visit the Rafah office daily, seeking assistance to meet their basic needs, such as food, water, mattresses, and sanitary products. However, Syam said the assistance they can offer is just a fraction of what is needed.

Syam lives in a classroom at a non-governmental organization, which shelters displaced persons. Like many others, she has been displaced multiple times and experienced personal loss, yet she continues to work every day. When she returns to the shelter, there is usually not enough fuel to cook food. Lately, she has been burning books for fuel.

“Supporting grassroots women’s organizations in Palestine is critical,” said Syam. “Without adequate support and funding, these organizations may struggle to continue providing essential services.” The implications of such funding shortfall are dire in an already unprecedented crisis. It could cut off access to vital resources and without their advocacy efforts, the voices of many women in Gaza would go unheard.

Syam also stressed on the need for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza and the provision of humanitarian aid, adding, “it is imperative to strengthen the role of civil society institutions, especially women’s organizations that have been working since the onset of the war, and to enhance partnership and coordination with international and UN agencies to make sure that gender issues are fully addressed in all humanitarian interventions.”

Women lifting other women amidst Myanmar’s economic crisis

Thiri Aung knows what it is like to grow up in an unstable economy.

“I was about 11 years old, and I remember my mum was carrying two cookie boxes filled with 45 Kyat bills and 90 Kyat bills. She was crying because the money we had, that the family had, we could no longer use,” she recalls. Myanmar had suddenly pulled two currency notes from circulation.

Three years after the military takeover on 1 February 2021, Myanmar is experiencing economic, political, and humanitarian crises affecting every aspect of life in the country. The economy has shrunk around 10 per cent since 2019, the poverty rate is at levels not seen for 15 years. Families are in deep financial distress and women are among the hardest hit.

Thiri Aung, a Yangon-based entrepreneur and founder of the women’s business support network, Women Transforming Myanmar (WTM), has partnered with UN Women to create sustainable livelihoods. She has designed the Transformative Feminist Leadership programme, which boosts women’s business skills and confidence.

Since the programme launched in September 2023, more than 520 women have already accessed support in-person and through the recently launched UNDP Myanmar e-learning portal.

“Our aim is to empower women entrepreneurs and women leaders of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises to lead social change and create more equitable, inclusive businesses,” said Thiri Aung.

For many of the women, it is the first time they have received leadership training or learned about gender equality. “Many women have opened up and talked about how their voices were unheard in their village and community just because they are women,” she added. “They feel safe sharing these experiences and they support each other.”

This goes to the heart of what inspired Aung to create WTM. “I wanted to help women not only start their businesses but sustain them in the long run, so that they could then create job opportunities for other women,” she said.

Women’s organizations on the frontlines of the war in Ukraine

For decades, Halyna Skipálska has worked toward an ambitious goal: to make Ukraine a better country, “where every woman is aware of her rights and can pursue her goals; a Ukraine where women live healthy and happy lives.”

Skipálska is the Executive Director of the Ukrainian Foundation for Public Health (UFPH), a national women-led organization supported by the United Nations Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF). The organization helps women, including pregnant women, single mothers and female-headed families, access quality social and healthcare services.

Since February 2022, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Skipálska and her colleagues became first responders, providing essential supplies, health services and psychosocial support to internally displaced people across Ukraine.

“In a matter of days, we transitioned from being a development organization to conducting humanitarian work on the front lines,” said Skipálska in a recent interview with WPHF.

Two years since the war broke out, millions of people remain internally displaced in Ukraine and 80 per cent of the nearly 6 million refugees and asylum seekers are women and children.

As reports of conflict-related sexual violence and serious violations of women’s rights poured in, Skipálska’s organization partnered with WPHF and UN Women Ukraine to create a virtual platform, the SafeWomen Hub to raise awareness and provide mental health support services to displaced women and girls, survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, and victims of human trafficking. The Hub also supported local women’s organizations to adapt to the evolving crisis and enhance their capacity to identify and serve survivors of violence.

Over the last two years, over 13,000 women and girls have received assistance through the platform, which operates through social media (mainly Facebook, Instagram and Telegram) and can be easily accessed with a smartphone or a tablet. There are eight mobile crisis teams offering support to internally displaced families and children, providing emergency response services, psychological counselling, legal advice, and more. They also help distribute humanitarian kits and essential items to displaced persons.

“If the war in Ukraine has proven anything, it is that civil society organizations are quicker, more flexible, better equipped, and more efficient than other national and international actors at closing gaps and addressing urgent needs, particularly in the first months of the war,” said Skipálska.

She is a strong advocate for recognizing and funding local women’s organizations to scale up the impact of humanitarian action on the ground: “By supporting grassroots organizations, we empower local communities and contribute to a more just and equitable society.”

*Note: Parts of this interview has been excerpted from an article published by the United Nations Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund

Making sure migrant women’s voices are heard in Colombia

More than 7 million people have left Venezuela since 2014, as a result of the political, socio-economical and humanitarian crisis. A vast majority of them are hosted by neighbouring countries, including Colombia, where almost 3 million Venezuelans are looking for opportunities.

Their journeys were difficult – many left Venezuela without their families and belongings, including documentation that would allow them to cross borders safely. Venezuelan women and girls faced heightened risk of sexual violence and human trafficking. When they reached a host country, they often experienced xenophobia and discrimination.

“Immigrating has been the most difficult thing for me. Not everyone can adapt to another place,” said Mayerling Cordero, who arrived in Colombia five years ago.

“The way men addressed me, because I was a woman and Venezuelan, was very hurtful.”

In 2020, Cordero joined community dialogues supported by UN Women. There she learned to recognize and support migrant and refugee women experiencing violence. She started organizing meetings in the living room of her house, offering them a safe space to come together and express themselves. She shared with them what she had learned about gender-based violence, immigration rules and procedures, and how to access health and education services.

Within two more years, Cordero started a local organization, ‘Machis Entrelazadas’, to promote women’s safety, mental health and self-care.

Through the ‘Beyond the flags, we are women’ programme, UN Women and the United States Office of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) has supported the work of 24 community-based organizations, such as 'Machis Entrelazadas’, on the Colombian Caribbean coast and on the southern border in the department of Nariño.

For Mayerling Cordero and other migrant women-led organizations, this support is critical: “It is very important that the leadership and participation of women's groups continue to be strengthened, because it allows them to have a clearer voice to communicate the problems of migrant women before State institutions.”

Note: Parts of this interview have been repurposed from an article published by UN Women LAC. Learn more here.